Every Christmas season, my great-grandfather, Domenico Gatti, would make the traditional holiday ‘fruitcake’ of central Italy called Pane Pepato.

Despite the best efforts of his two daughters.

Each year, Nonno Domenico would harvest the trees on his land, in turn, for almonds, hazelnuts and walnuts. He would place them into a cloth sack that he would hang from a hook on the high beam in the ceiling of his home on Vicolo Zancati in the medieval quarter of Anagni, 40 miles south of Rome.

In late September and early October, when he harvested the grape from his vineyards in the hills outside of town — an area called “Ai Monti,” translated into English as ‘in the mountains’ – to make his wine, he would set aside a small selection of the healthiest fruit to hang and dry into raisins.

After the grape were crushed but before their juice would start fully fermenting into wine, Domenico drew off a few gallons of the ‘mosto’ – unfermented grape juice – and brought it to a simmer in a copper cauldron over an open fire, reducing the quantity to half of its original volume. Rich in natural sugar, this would be the ‘glue’ that would hold together his prized Pane Pepato.

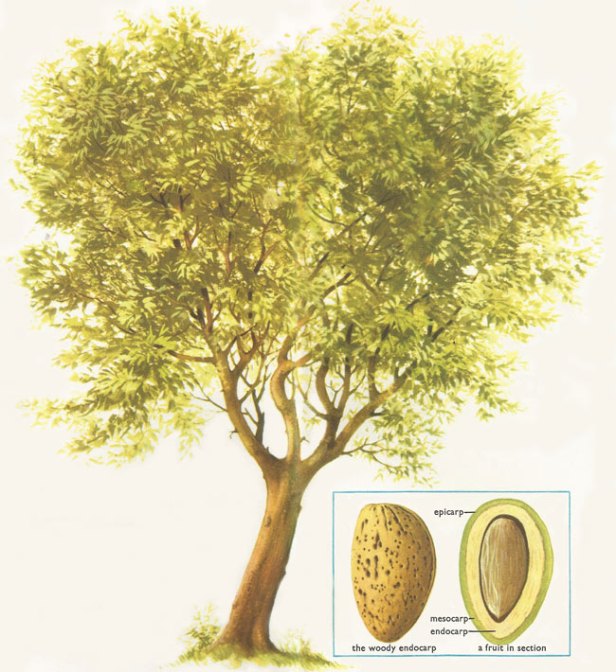

Pane Pepato, back in the day, was an important source of calories and nutrients to help the Italian peasant farmer get through the winter. It is traditionally made with almonds, walnuts, hazelnuts, raisins, citron, cooked must, orange zest, and a dash of salt and black pepper. It takes its name Pane Pepato from that addition of pepper.

But if it was up to Domenico’s hungry daughters, Maria and Quintilia, the fixings for Pane Pepato would not have made it to the holiday season.

Maria, my grandmother, was a bit of a wild child in her youth, known for her penchant to go bare foot and stash her ‘Cioce,’ the traditional laced leather shoes worn by our people and which gave the region its nickname, La Ciociaria.

Young Maria liked to climb trees too, especially almond trees. In the spring when almonds are still green, before the shells harden and dry into the shells and nuts we are so familiar with, they are, for a brief period, tender, tart, and crisp. This was Maria’s favorite snack, much to her father’s chagrin. “Lascia le stare,” he would admonish his hungry young daughter – leave them be! We need them for the winter and our Pane Pepato!

Quntilia was younger, and slightly more discreet. She might not have been caught climbing the trees in spring, but come autumn – just as hungry – she knew where her beloved “Tata” (our dialect for Papa or Dad) kept his stash. More importantly, she knew where he kept the hooked pole that helped him raise and lower the cloth sack as needed. She employed it to poke a hole in the side of the sack, then would craftily whack it on the side to let a few nuts fall out for a pleasing daily snack. Come early December, Domenico found his Pane Pepato provisions seriously diminished!

The very fact that I know this story of late 19th/early 20th century escapades is testament to the storytelling culture of Anagni that persisted into the 1980s when I first visited Anagni and was regaled with these tales.

But the Pane Pepato itself was another story.

When my Nana Maria left Anagni in 1920, she took the ancient, cherished recipe with her. Over the years since, things changed in Anagni. Nana Maria also adapted to her new homeland in The Bronx, NY, but she made few if any change to her Pane Pepato. The recipe she handed down to her son Fiore, the uncle who taught me, was strictly old school. When my cousin Joanne was studying abroad and visited Anagni in 1971, she brought ‘our’ Panpepato to Maria’s brother Eraldo, who at the same time both rejoiced and scolded his wife – ‘this is what Pane Pepato is supposed to be!’ Point of pride was that it was dense enough to slice thinly, and take on the appearance of stained glass. My version has lost that charm, but not the flavor.

In the old country, techniques and methods changed over the years – as times grew better and Anagni grew wealthier, they added chocolate, sometimes honey, sometimes brandy. But Nana Maria’s Pane Pepato – as executed by her, by Uncle Fiore, by me, and from what I hear my cousin Joanne this coming weekend – is the historic (i.e. ‘poor man’s’) recipe. When I bring it with me on my frequent visits to Anagni, I get no complaints. In fact, only compliments.

After a long dry spell, I made Pane Pepato again this year. Very happy with the results. And the tradition.

Some American cousins only remember the phonetic pronunciation — ‘pana-papa,’ or similar. It is different, it is historic, but no matter how your pronounce it, it is tasty – and always respected!

Thanks, Lars. I didn’t know thistory. Vey nice. Oh, and welcome home.

LikeLike

Hello! Lovely story, any chance you. It share the recipe please?

LikeLike